There's so much to feast on in Issue 4 of the online book review magazine Shiny New Books out today. I've only just begun to delve, but have already enjoyed Simon's review of Essays on the Self by Virginia Woolf and (having just finished Middlemarch for the first time) Lory Widmer Hess's thoughts on The Road to Middlemarch: My Life with George Eliot by Rebecca Mead.

I was really pleased to contribute my review of Claire of the Sea Light, Edwidge Danticat's lyrical tale of the harshness of life in a Haitian village. As an enchanted girl goes missing by moonlight, her family and friends who join in the search for her remember loved ones they have already lost. You can read more about this absorbing book here.

There's much more to explore, including a competition to win (unsurprisingly!) some lovely books. But beware - your wishlist is in danger of extending exponentially!

Thursday 29 January 2015

Wednesday 28 January 2015

Theatre Review: Who is Dory Previn? - Tobacco Factory Theatre, Bristol

This review was originally written for The Public Reviews

Kate Dimbleby walks on stage and talks of screaming on a plane and immediately it becomes clear that if we don’t already know about Dory Previn, whose words these are, then we should. Here is a woman who has spoken of extraordinary things and written extraordinary songs and yet today there is little knowledge of her.

Dory was a singer-songwriter, thrice married and most famously to the composer André Previn, who poured her life into songs naked with pain but accessible through humour. Born Dorothy Langan in New Jersey in 1925 to a strict Irish Catholic family, her father’s First World War experiences were so extreme that they led to him boarding his family into a room for several months. Yet, as soon as young Dorothy displayed a talent for dancing, he turned pushy parent and took her to Hollywood. There, after a series of misadventures, she found work as a lyricist for MGM, first collaborating with and then marrying Previn. But, as her mental frailty became more overt, he eventually left her for the young ingénue Mia Farrow.

Dimbleby recounts Dory’s life through a mixture of song, autobiographical narration and her own explanation of how she came to know Dory’s songbook. She’s accompanied on the piano by Naadia Sheriff who harmonises beautifully and partners Dimbleby in delivering key lines of narrative. It’s an entertainingly assured combination; transported from the New York cabaret circuit to the mean floorboards of the Tobacco Factory, this is no fly-by-night venture. The show has been developed over the course of six years and, in bringing it to Bristol, Dimbleby is performing in her new hometown.

Under the direction of Cal McCrystal (One Man, Two Guv’nors), many of the autobiographical details of Dory’s difficult life are glossed over, her abortions briefly mentioned and some of her darkest moments treated lightly. But this was often Dory’s approach too; although Beware Of Young Girls is a map of her heartbreak over losing her husband to Farrow and her insecurity is echoed in Lemon Haired Ladies, Twenty Mile Zone is a humorous take on her subsequent breakdown. What could be more natural, after all, than screaming on your own in a car when your life has fallen apart? Or screaming on a plane when you are terrified of flying?

There are more tentatively hopeful songs, too. Lady With The Braid captures the tender nervousness of a first night with a new love; “there’s this coverlet my cousin hand crocheted/do you mind if the edges are frayed/would you like to unfasten my braid”. Joby Baker, the man who became her third husband was with her until her death in 2012, but Dory came to realise that human beings can’t be bound and our only true security lies within ourselves.

More questions are raised than can possibly be answered. Why, for example, does André Previn apparently escape scot-free from blame for his affair, with all Dory’s vitriol being reserved for Farrow?

In the end it is the songs and, in particular their lyrics, which are triumphant. The audience on the first night is a knowledgeable and appreciative one, calling for an encore. But, for those coming afresh to Dory Previn, this show will leave you wanting to find out more. Dimbleby’s passion for her subject provides an affectionate, tantalising glimpse into the life of a talented yet deeply troubled woman unafraid to lay herself bare through song.

Reviewed on 23rd January 2015 | Photo Ian Douglas

For upcoming dates, visit Kate's website

Wednesday 21 January 2015

Personal Picks: The Independent Bath Literature Festival 2015

It hardly seems possible, but it's the twentieth anniversary of the Bath Literature Festival. Starting out as a couple of dozen talks in 1995, it's now grown to a ten-day programme of more than two hundred authors.

It's also comedian, writer and jumpsuit wearer* Viv Groskop's second year as Artistic Director. In 2014, she indefatigably introduced, interviewed and performed at so many events, it seemed she must have hired a team of lookalikes to help her out.

This year, there are some fantastic headline novelists; Kazuo Ishiguro in particular has caught my eye because The Buried Giant, his first novel in a decade, is due out in the spring. And the tribute to

Ted Hughes, who took part in that very first festival, promises to be an inspiring occasion. Included in the glittering line up - amongst others - are his daughter Frieda Hughes and the performance poet Kate Tempest.

Well-publicised headliners tend to sell out quickly, so for this years picks, I've decided to concentrate on other parts of the programme; events which might take place at odd times of day or have escaped your attention in a brochure packed full of literary goodies. The speakers you might take a bit of a punt on often turn out to be the most unexpectedly wonderful of them all, so if you've missed out on one of those sold-out headline events, fear not.

My first pick is Mark Bostridge discussing Vera Brittain and the First World War. Testament of Youth is probably the book I've reread more than any other, having first discovered it through the TV series starring Cheryl Campbell in the late 1970s. I'm running scared of seeing the new film version of her life for fear of disappointment, but have no such qualms about listening to Vera's biographer tell her remarkable story.

Bath Spa has an excellent record of turning out prize-winning debut authors (think Nathan Filer's The Shock of the Fall). This year, two debut novelists from its Creative Writing MA, Anna Freeman and Emma Hooper, will be in conversation in both the Guildhall and Keynsham library, about their books and the path to publication. I'm about to begin reading Hooper's extraordinary-sounding Etta and Otto and Russell and James, the story of one woman's epic walk across Canada to the ocean. And I like the unusual premise of Freeman's The Fair Fight, which explores the world of female pugilists in 18th century Bristol.

Talking of extraordinary stories, that truth is often stranger than fiction is perfectly illustrated by the life of Sophia Duleep Singh, a princess in exile who became one of the most charismatic figures in the suffragette movement. If, like me, you've never heard of Sophia before, BBC Radio 4 presenter Anita Anand's talk about her book Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary should enlighten you. I particularly like her contention that today Sophia would be 'lobbing a brick through Russell Brand's window', for encouraging young people not to vote, because so many died to give us that privilege.

There are two events on Monday 2nd March which particularly fascinate me; firstly the life of Stefan Zweig will be presented by George Prochnik at BRLSI. In the early 1930s, Zweig was the most widely translated living author in the world, and at one point he was exiled in Bath. I have to admit to not having read any of his books yet, but having discovered his brilliance through Wes Anderson's film of The Grand Budapest Hotel, I'm vowing to put this right in 2015.

Later the same evening, Nikesh Shukla will be talking to Niven Govinden and Sathnam Sanghera about the Elephant in the Room that is the difficulty in being pigeon-holed as British Asian authors in a society that only wants to know their thoughts on race and immigration. With recent, shocking events and multiculturalism so much in the spotlight, this promises to be an essential and illuminating debate.

Last year saw the first Bliss Lectures - with bliss being anything from Tolstoy to badgers. And this year they're back by popular demand, with Kate Mosse advocating adventure fiction and Fay Weldon singing the praises of editing. My Bliss Pick goes to Elif Shafak talking Turkey because The Architect's Apprentice is currently wrestling with Etta and Otto and Russell and James for the top of my reading pile. And because Shafak is mesmerising to listen to on any subject from feminism, literature and freedom to the conflicting feelings she has for her homeland.

I listened to Tim Dee discussing his book, The Running Sky, a few years ago and was inspired to buy it immediately, despite previously having no particular interest in bird watching. His prose is so extraordinary that it crosses into poetry and induced in me a road-to-Damascus moment, bird-wise. So his conversation with Mark Cocker, who has written Birds and People about our relationship with birds, wildlife and nature in general, sounds unmissable whether you're an established twitcher or a complete novice like me.

Continuing the horizon-broadening theme, my final pick is Around the World in 10 Books. Apparently only 3% of books published in the UK each year are translations. With this tunnel vision, we deny ourselves so much that is wonderful in world literature. Ann Morgan's Reading the World:Confessions of a Literary Explorer covers fiction from 196 countries and, in collaboration with publisher Scott Pack, she will be presenting 10 of her latest international discoveries. Your mind might just be expanded which, after all, is just what great literature can do - like drugs but without the side-effects.

*although I didn't see her in one at the 2014 Festival.

Images courtesy of Bath Festivals, Viv Groskop, Bloomsbury, The Independent, English Pen, NHBS, readingtheworld.com

It's also comedian, writer and jumpsuit wearer* Viv Groskop's second year as Artistic Director. In 2014, she indefatigably introduced, interviewed and performed at so many events, it seemed she must have hired a team of lookalikes to help her out.

This year, there are some fantastic headline novelists; Kazuo Ishiguro in particular has caught my eye because The Buried Giant, his first novel in a decade, is due out in the spring. And the tribute to

Ted Hughes, who took part in that very first festival, promises to be an inspiring occasion. Included in the glittering line up - amongst others - are his daughter Frieda Hughes and the performance poet Kate Tempest.

Well-publicised headliners tend to sell out quickly, so for this years picks, I've decided to concentrate on other parts of the programme; events which might take place at odd times of day or have escaped your attention in a brochure packed full of literary goodies. The speakers you might take a bit of a punt on often turn out to be the most unexpectedly wonderful of them all, so if you've missed out on one of those sold-out headline events, fear not.

My first pick is Mark Bostridge discussing Vera Brittain and the First World War. Testament of Youth is probably the book I've reread more than any other, having first discovered it through the TV series starring Cheryl Campbell in the late 1970s. I'm running scared of seeing the new film version of her life for fear of disappointment, but have no such qualms about listening to Vera's biographer tell her remarkable story.

Bath Spa has an excellent record of turning out prize-winning debut authors (think Nathan Filer's The Shock of the Fall). This year, two debut novelists from its Creative Writing MA, Anna Freeman and Emma Hooper, will be in conversation in both the Guildhall and Keynsham library, about their books and the path to publication. I'm about to begin reading Hooper's extraordinary-sounding Etta and Otto and Russell and James, the story of one woman's epic walk across Canada to the ocean. And I like the unusual premise of Freeman's The Fair Fight, which explores the world of female pugilists in 18th century Bristol.

Talking of extraordinary stories, that truth is often stranger than fiction is perfectly illustrated by the life of Sophia Duleep Singh, a princess in exile who became one of the most charismatic figures in the suffragette movement. If, like me, you've never heard of Sophia before, BBC Radio 4 presenter Anita Anand's talk about her book Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary should enlighten you. I particularly like her contention that today Sophia would be 'lobbing a brick through Russell Brand's window', for encouraging young people not to vote, because so many died to give us that privilege.

There are two events on Monday 2nd March which particularly fascinate me; firstly the life of Stefan Zweig will be presented by George Prochnik at BRLSI. In the early 1930s, Zweig was the most widely translated living author in the world, and at one point he was exiled in Bath. I have to admit to not having read any of his books yet, but having discovered his brilliance through Wes Anderson's film of The Grand Budapest Hotel, I'm vowing to put this right in 2015.

Later the same evening, Nikesh Shukla will be talking to Niven Govinden and Sathnam Sanghera about the Elephant in the Room that is the difficulty in being pigeon-holed as British Asian authors in a society that only wants to know their thoughts on race and immigration. With recent, shocking events and multiculturalism so much in the spotlight, this promises to be an essential and illuminating debate.

Last year saw the first Bliss Lectures - with bliss being anything from Tolstoy to badgers. And this year they're back by popular demand, with Kate Mosse advocating adventure fiction and Fay Weldon singing the praises of editing. My Bliss Pick goes to Elif Shafak talking Turkey because The Architect's Apprentice is currently wrestling with Etta and Otto and Russell and James for the top of my reading pile. And because Shafak is mesmerising to listen to on any subject from feminism, literature and freedom to the conflicting feelings she has for her homeland.

I listened to Tim Dee discussing his book, The Running Sky, a few years ago and was inspired to buy it immediately, despite previously having no particular interest in bird watching. His prose is so extraordinary that it crosses into poetry and induced in me a road-to-Damascus moment, bird-wise. So his conversation with Mark Cocker, who has written Birds and People about our relationship with birds, wildlife and nature in general, sounds unmissable whether you're an established twitcher or a complete novice like me.

Continuing the horizon-broadening theme, my final pick is Around the World in 10 Books. Apparently only 3% of books published in the UK each year are translations. With this tunnel vision, we deny ourselves so much that is wonderful in world literature. Ann Morgan's Reading the World:Confessions of a Literary Explorer covers fiction from 196 countries and, in collaboration with publisher Scott Pack, she will be presenting 10 of her latest international discoveries. Your mind might just be expanded which, after all, is just what great literature can do - like drugs but without the side-effects.

*although I didn't see her in one at the 2014 Festival.

Images courtesy of Bath Festivals, Viv Groskop, Bloomsbury, The Independent, English Pen, NHBS, readingtheworld.com

Wednesday 14 January 2015

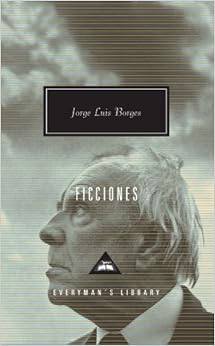

Reading the Classics: Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges

Studying for my online course, The Fiction of Relationship, took a back seat over Christmas and I'm now so far behind that the programme has officially finished. Happily, I discovered all my links were still working and was soon absorbed back into the world of Brown University and Professor Weinstein's video lectures on Borges's Ficciones.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899 - 1986) was an Argentinian writer and translator of short stories, essays and poetry. His work is widely regarded as abstract and esoteric, making him an unusual choice for this particular syllabus, as course tutor Professor Weinstein freely admits. His argument is that Borges regularly takes the theme of relationship into strange, uncharted precincts.

In Ficciones, one of his most well-known short story collections, Borges stretches and destabilises accepted notions of identity and frequently introduces a 'who am I' riddle into his narrative. The Shape of the Sword, for example, contemplates an Englishman with a face 'traversed by a vengeful scar', but our perceptions of this man are completely turned around by the ending.

Ideas come first for Borges, taking on a life of their own. In the story Funes The Memorius, Ireneo Funes's mind is altered by a fall from his horse. He is no longer capable of abstract thought and is irritated to find that a dog seen from the side at three-fourteen in the afternoon is described as the same dog seen from the front at three-fifteen. Funes has a prodigious memory and observes each momentary perception in the minutest detail. He'd be a natural on any mindfulness course, but Borges captures the exhaustion of life at this extreme:

Borges will also take a familiar story and explode it. The House of Asterion tells the tale of Theseus and the Minotaur from a different point of view and Three Versions of Judas suggests that, far from being a figure we should revile, Judas sacrificed himself to deliver the betrayal necessary for Christ's salvation. If we are all human pieces of a pre-ordained design, our world view is completely reversed; every negligence becomes deliberate and every death a suicide. As in The Traitor and The Hero, we fulfill the role that has been scripted for us, like actors in a play.

The Garden of Forking Paths is widely viewed as one of Borges's masterpieces and Weinstein suggests that the choice of forking paths we take throughout our own lives shapes who we are. We're in a constant state of evolution; he uses the image of a developing Polaroid film as a metaphor for identity emerging and gradually being defined.

A displaced Chinese spy fleeing capture has to convey to his masters the details of a city that should be bombed. Visiting the home of a man whose name he picks out of a phone book, he comes to view him as no less a genius that Goethe. This man has solved the mystery of a labyrinthine book written by the spy's own ancestor, and explains it to him:

Ficciones is a densely-written yet riveting collection of short stories which expose the wiring of their construction and unlock possibilities of time and space. Borges often appears to be playing philosophical games; beginning by posing metaphysical conundrums to be unravelled and ending by confounding any expectations you may have had of the outcome. While I immediately understood why Borges is seen as the father of magical realism, it has taken Professor Weinstein's lectures to explain to me the aspects of these abstract works which reflect upon our own identity and relationships.

Image of Borges in 1951 courtesy of Wikipedia, Ficciones courtesy of Amazon. I read Penguin Modern Classics' 'Fictions' by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley and available from Wordery.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899 - 1986) was an Argentinian writer and translator of short stories, essays and poetry. His work is widely regarded as abstract and esoteric, making him an unusual choice for this particular syllabus, as course tutor Professor Weinstein freely admits. His argument is that Borges regularly takes the theme of relationship into strange, uncharted precincts.

In Ficciones, one of his most well-known short story collections, Borges stretches and destabilises accepted notions of identity and frequently introduces a 'who am I' riddle into his narrative. The Shape of the Sword, for example, contemplates an Englishman with a face 'traversed by a vengeful scar', but our perceptions of this man are completely turned around by the ending.

Ideas come first for Borges, taking on a life of their own. In the story Funes The Memorius, Ireneo Funes's mind is altered by a fall from his horse. He is no longer capable of abstract thought and is irritated to find that a dog seen from the side at three-fourteen in the afternoon is described as the same dog seen from the front at three-fifteen. Funes has a prodigious memory and observes each momentary perception in the minutest detail. He'd be a natural on any mindfulness course, but Borges captures the exhaustion of life at this extreme:

With one quick look, you and I perceive three wine glasses on a table; Funes perceived every grape that had been pressed into the wine and all the stalks and tendrils of its vineyard. He knew the forms of the clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memory with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once, or with the feathers of spray lifted by an oar on the Rio NegroIn The Secret Miracle, Borges bends the perception of time in a different way, as his protagonist Hladik, facing a firing squad, wishes to complete an unfinished play before his imminent death. Conventions of time and place are transcended as his mind constitutes his freedom, but only for a finite period. In Borges's world, bills are paid and, ultimately, there is no cheating. In the end, Weinstein posits, we are all standing in front of that firing squad.

Borges will also take a familiar story and explode it. The House of Asterion tells the tale of Theseus and the Minotaur from a different point of view and Three Versions of Judas suggests that, far from being a figure we should revile, Judas sacrificed himself to deliver the betrayal necessary for Christ's salvation. If we are all human pieces of a pre-ordained design, our world view is completely reversed; every negligence becomes deliberate and every death a suicide. As in The Traitor and The Hero, we fulfill the role that has been scripted for us, like actors in a play.

The Garden of Forking Paths is widely viewed as one of Borges's masterpieces and Weinstein suggests that the choice of forking paths we take throughout our own lives shapes who we are. We're in a constant state of evolution; he uses the image of a developing Polaroid film as a metaphor for identity emerging and gradually being defined.

A displaced Chinese spy fleeing capture has to convey to his masters the details of a city that should be bombed. Visiting the home of a man whose name he picks out of a phone book, he comes to view him as no less a genius that Goethe. This man has solved the mystery of a labyrinthine book written by the spy's own ancestor, and explains it to him:

In all fictions, each time a man meets diverse alternatives, he chooses one and eliminates the others; in the work of the virtually impossible-to-detangle Ts'ui Pen, the character chooses - simultaneously - all of them. He creates, thereby, 'several futures', several times, which themselves proliferate and fork. That is the explanation for the novel's contradictions. Fang, let us say, has a secret; a stranger knocks at his door; Fang decides to kill him. Naturally, there are various possible outcomes - Fang can kill the intruder, the intruder can kill Fang, they can both live, they can both be killed, and so on. In Ts'ui Pen's novel, all the outcomes in fact occur; each is the starting point for further bifurcations. Once in a while, the paths of that labyrinth converge: for example, you come to this house, but in one of the possible pasts you are my enemy, in another my friend.Borges suggests that no choice is definitive, each is the beginning of another choice. He is exploring the territory of 'The Road not Taken' by Robert Frost and defying Western logic, the binary of choosing A over B. In more contemporary terms, he has the outlook of a video games designer.

Ficciones is a densely-written yet riveting collection of short stories which expose the wiring of their construction and unlock possibilities of time and space. Borges often appears to be playing philosophical games; beginning by posing metaphysical conundrums to be unravelled and ending by confounding any expectations you may have had of the outcome. While I immediately understood why Borges is seen as the father of magical realism, it has taken Professor Weinstein's lectures to explain to me the aspects of these abstract works which reflect upon our own identity and relationships.

Image of Borges in 1951 courtesy of Wikipedia, Ficciones courtesy of Amazon. I read Penguin Modern Classics' 'Fictions' by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley and available from Wordery.

Sunday 4 January 2015

Guest Book Review: Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro is already in the news this year with The Buried Giant, his first novel in a decade, due out this spring. He'll be talking about it at the Bath Literature Festival on 6th March 2015; set in a mythical post-Roman Britain, it sounds intriguingly different from his other books.

Ishiguro won The Man Booker Prize for The Remains of the Day back in 1989, when it was still simply known as The Booker. And he's been nominated three more times.

One of these nominations was in 2005 for Never Let Me Go. My guest reviewer (and younger daughter) Imogen Hayes, first saw this as the 2010 film starring Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield and Keira Knightley.

She loved the film but, inspired to read the book, declared it even better. That's my girl...and here's the review she wrote for her English Literature AS level.*

Children of Hailsham House must take extreme care of their health, produce extensive collections of artwork and never stray outside its borders. Like other children, they are frightened of the woods and grow excited at the thought of jumble sales. Yet they have no surnames, parents or family history; only guardians to serve as parental figures. This is why in the enclosed world of Kazuo Ishiguro’s dystopian novel, friends are all that Hailsham students have in their lives. Unlike other children, their existence has a single focus; a sole dark and disturbing purpose.

Ishiguro’s previous novels have won him international acclaim and many honours including the Booker Prize, the Whitbread Book of the Year Award and an OBE for services to literature. Never Let Me Go is his sixth novel, set in an alternative version of late 1990s England, where Kathy H, Tommy D and Ruth are students of Hailsham, desperately seeking to discover more about their strange world.

Narrated by Kathy, the story of her early life is told in a fragmented series of memories. She recalls her Hailsham days fondly and in astonishingly minute detail; the secret pathways, snatches of overheard conversation between guardians and the secluded pond where she and Tommy would puzzle over the purpose of ‘The Gallery’. In the present day Kathy is a Carer. She reflects on her memories with retrospective wisdom, as she attempts to answer troubling questions about her existence and gain solace in the past, clinging to the memories of her loved ones.

Kathy, Tommy, Ruth and their peers live in a state of limbo after leaving the sanctity of Hailsham for The Cottages, when it is only a matter of time before they must begin to make their troubling ‘donations’. It is here that the closely intertwined relationship between the three friends becomes more complex. This is their first experience with the outside world and Kathy records it with an observant eye, watching as Ruth childishly endeavours to impress older, more experienced housemates, or Veterans, from other estates; copying their mannerisms, second-hand from the cheesy American sitcoms they watch on television.

During this time Kathy, Tommy and Ruth are free to roam deep into the countryside and travel into the town, where they tentatively interact with people from the outside world, so-called ‘Originals’. They are strangely disconnected from the society that created them, where people know the real cost of their advanced healthcare, but neglect to speak about it. In this way, Ishiguro holds up a bleak mirror to humanity, reflecting on how far we are willing to go to preserve human life, no matter how questionable the ethics may be. Perhaps Never Let Me Go is not dystopian fiction, depicting a distant corrupted future; but is just an extension of our existing society, not so far from reality.

Ishiguro’s writing is clever and powerfully moving, without sentimentality or manipulation of the reader’s feelings. As their time at The Cottages comes to a close, the friends face being torn apart in an uncertain future, as Kathy comments

* with minor alterations

Never Let Me Go is published in paperback (304 pp) by Faber & Faber.

Kazuo Ishiguro photo courtesy of Matt Carr/Getty Images. Book cover/film still courtesy of Wikipedia.

Ishiguro won The Man Booker Prize for The Remains of the Day back in 1989, when it was still simply known as The Booker. And he's been nominated three more times.

One of these nominations was in 2005 for Never Let Me Go. My guest reviewer (and younger daughter) Imogen Hayes, first saw this as the 2010 film starring Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield and Keira Knightley.

She loved the film but, inspired to read the book, declared it even better. That's my girl...and here's the review she wrote for her English Literature AS level.*

Children of Hailsham House must take extreme care of their health, produce extensive collections of artwork and never stray outside its borders. Like other children, they are frightened of the woods and grow excited at the thought of jumble sales. Yet they have no surnames, parents or family history; only guardians to serve as parental figures. This is why in the enclosed world of Kazuo Ishiguro’s dystopian novel, friends are all that Hailsham students have in their lives. Unlike other children, their existence has a single focus; a sole dark and disturbing purpose.

Ishiguro’s previous novels have won him international acclaim and many honours including the Booker Prize, the Whitbread Book of the Year Award and an OBE for services to literature. Never Let Me Go is his sixth novel, set in an alternative version of late 1990s England, where Kathy H, Tommy D and Ruth are students of Hailsham, desperately seeking to discover more about their strange world.

Narrated by Kathy, the story of her early life is told in a fragmented series of memories. She recalls her Hailsham days fondly and in astonishingly minute detail; the secret pathways, snatches of overheard conversation between guardians and the secluded pond where she and Tommy would puzzle over the purpose of ‘The Gallery’. In the present day Kathy is a Carer. She reflects on her memories with retrospective wisdom, as she attempts to answer troubling questions about her existence and gain solace in the past, clinging to the memories of her loved ones.

Kathy, Tommy, Ruth and their peers live in a state of limbo after leaving the sanctity of Hailsham for The Cottages, when it is only a matter of time before they must begin to make their troubling ‘donations’. It is here that the closely intertwined relationship between the three friends becomes more complex. This is their first experience with the outside world and Kathy records it with an observant eye, watching as Ruth childishly endeavours to impress older, more experienced housemates, or Veterans, from other estates; copying their mannerisms, second-hand from the cheesy American sitcoms they watch on television.

During this time Kathy, Tommy and Ruth are free to roam deep into the countryside and travel into the town, where they tentatively interact with people from the outside world, so-called ‘Originals’. They are strangely disconnected from the society that created them, where people know the real cost of their advanced healthcare, but neglect to speak about it. In this way, Ishiguro holds up a bleak mirror to humanity, reflecting on how far we are willing to go to preserve human life, no matter how questionable the ethics may be. Perhaps Never Let Me Go is not dystopian fiction, depicting a distant corrupted future; but is just an extension of our existing society, not so far from reality.

Ishiguro’s writing is clever and powerfully moving, without sentimentality or manipulation of the reader’s feelings. As their time at The Cottages comes to a close, the friends face being torn apart in an uncertain future, as Kathy comments

It never occurred to me that our lives, until then so closely interwoven, could unravel and separate.Kathy’s chance to experience the love and happiness she craved for her entire life is tainted by the fear that it has all been left too late. Though her hope is constantly being eroded, she refuses to pity herself, as she discovers and accepts the purpose of her existence. Ishiguro’s refusal to back up the plot with scientific plausibility allows the reader to focus solely on the lives of the characters and their emotions, and to view the natural human life span in a de-familiarised sense.

* with minor alterations

Never Let Me Go is published in paperback (304 pp) by Faber & Faber.

Kazuo Ishiguro photo courtesy of Matt Carr/Getty Images. Book cover/film still courtesy of Wikipedia.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)