Translated Fiction

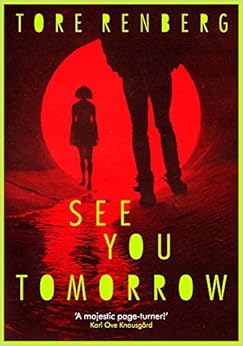

See You Tomorrow

Also translated into English for the first time is Tore Renberg. Already an established writer and broadcaster in his native Norway, Renberg has penned See You Tomorrow, a fast-paced, gritty and frequently hilarious thriller full of flawed and idiosyncratic characters.

The Master and Margarita

Translated fiction and classic literature all-in-one. I finally got round to reading Bulgakov's surreal examination of life in Stalinist Russia, juxtaposed with Pontius Pilate overseeing the trial of Yeshua. It's philosophical, playful and generally just all-round brilliant; tellingly, the Devil gets the best lines.

2014 Costa First Novel Award

I've read some excellent debut novelists in the English language too, including three of the four shortlisted for the 2014 Costa First Novel award (only Mary Costello's Academy Street to go).

Chop Chop

Simon Wroe's novel, endearingly narrated by lowest-of-the-low commis chef Monocle, is a bleakly funny, vicious and ultimately poignant dissection of the hell that is a professional kitchen.

Also shortlisted is Carys Bray's heart-rending debut about the devastating affect of the loss of a child. The Bradleys are a Mormon family living in the north-west of England. When their young daughter Issy falls ill with meningitis there are far reaching reverberations; many tears but some unexpected laughter too.

Elizabeth is Missing

Think of forgetting so much that you might not even recognise your own daughter and you'll begin to identify with the bewildering world of Maud, the elderly narrator of Emma Healey's first novel. Maud is forgetful and easily confused, but one thing she does know is that her friend Elizabeth is missing. And puzzling over her whereabouts awakens a mystery from Maud's past; the unsolved disappearance of her older sister Sukey.

Meant-to-Reads

The best of the books I meant to read when they were published in 2013, but only got round to this year.

The Shock of the Fall

A family's loss and the struggle to come to terms with mental illness, told from the inside. Nathan Filer not only won Costa's First Novel Award in 2013, but was also selected as their overall Book of the Year.

This one is personal (my review tells you why). Incredibly hard to read, but I'm so glad I did.

Rediscovered in 2013, John Williams's story of the life and times of a professor of literature at the University of Columbia was Waterstone's Book of the Year. A slow burn story, but once it takes hold, it doesn't let you go.

The Goldfinch*

I'm shocked to find I haven't reviewed this, probably because I read it over the summer holidays. Donna Tartt's epic has been criticised for being baggy and over-long, but has to be included because I became completely besotted with it. A future classic and my favourite book on the 2014 Baileys Prize shortlist, even though it didn't win.

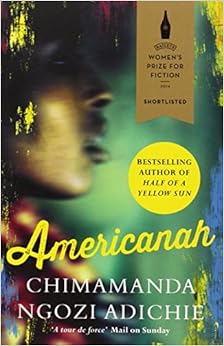

Americanah

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's novel about race and identity has at its heart the tender love story of Ifemelu and Obinze (I loved this almost as much as The Goldfinch).

It's a story about twin daughters Esma and Pembe, the divergent roles that fate has decreed for them and a very real tragedy which is not all that it seems.

New Writing

The Goldfinch*

I'm shocked to find I haven't reviewed this, probably because I read it over the summer holidays. Donna Tartt's epic has been criticised for being baggy and over-long, but has to be included because I became completely besotted with it. A future classic and my favourite book on the 2014 Baileys Prize shortlist, even though it didn't win.

Americanah

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's novel about race and identity has at its heart the tender love story of Ifemelu and Obinze (I loved this almost as much as The Goldfinch).

Honour

Elif Shafak's mystical writing combines sympathy for the conflict between the traditional and new in her native Turkey, with a wider understanding derived from her own crossing of the cultural divide.

It's a story about twin daughters Esma and Pembe, the divergent roles that fate has decreed for them and a very real tragedy which is not all that it seems.New Writing

This densely plotted, fiendishly intelligent espionage thriller by Edward Wilson reminds me why I should read more in this genre. If densely plotted, fiendishly intelligent espionage thrillers are a genre, that is. If not, then they should be.

Man at the Helm

The first novel from Nina Stibbe, author of the warm and witty collection of letters, Love, Nina, is an entertaining tale of divorce and village life in the 1970s, seen through the eyes of nine-year-old Lizzie Vogel.

The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy

If you enjoyed Rachel Joyce's The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, then you'll love this companion novel which tells the story of Harold's journey from Queenie's point of view. Poignant, entertaining and deftly profound.

Amy Mason is a funny and unexpected new voice. I saw her staging of The Islanders last year at Bristol Old Vic, and was looking forward to seeing where she was going next. Now she's won the Dundee International 2014 Book Prize with The Other Ida, the story of one young woman coming to terms with the death of her alcoholic mother.

The scariest category of all. What if a book you've loved doesn't live up to expectations second or third time around? Here are three that did:

I've read this book several times since watching the BBC TV series in the 1970s, but it felt very apt to be rereading it on the centenary of the outbreak of World War One. A deeply affecting memoir which brings home the personal sacrifice and devastating tragedy suffered by so many at the heart of a lost generation.

Jane Eyre

I didn't instantly fall in love with Charlotte Bronte's independently spirited orphan when I first read Jane Eyre at school, but have come to love her since. And rereading this novel for my online course only deepened my admiration for a mould-breaking woman ahead of her time.

To The Lighthouse

That this is my favourite Virginia Woolf novel was confirmed by rereading. Woolf's prose is as sublime as ever and (perhaps because of my own advancing years) I found a deeper connection this time to her portrayal of her parents in the form of Mr and Mrs Ramsay.

* The Goldfinch is the only book here that I haven't written a full review for.